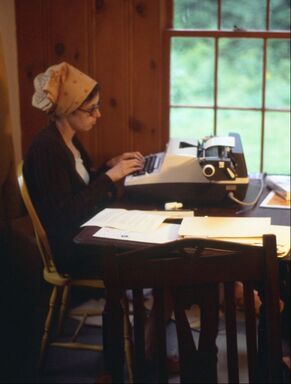

Me, shortly after my days at Penn

Me, shortly after my days at Penn I accepted an invitation to include an article based on my dissertation in a book of essays--a propitious start to an academic career, and my next move should have been to find a publisher for the dissertation itself. But like many of my cohort, I was deflected by the professional Darwinism of the 1970s, when the MacArthur Foundation had funded graduate students in the humanities so lavishly that the balance between supply and demand for tenure-track academic positions all around the country had been upset. There were two openings that year in the Philadelphia area, both with red flags. I had a delightful interview for one, but then the funding dried up as they had warned me it might and the job evaporated; the other, a one-year part-time position, went to someone else.

Meanwhile, something far more terrifying than the prospect of unemployment happened: My three-year-old daughter was stricken with h. flu meningitis and hospitalized for several weeks. Children are now routinely vaccinated against this dread disease, but at the time the only option was an extended course of intravenous antibiotics, which did not always work, and which even when it did could leave victims seriously impaired. Many of the women whose life stories I was reading had lost child after child to infectious disease, and I spent a lot of time at my daughter’s bedside wondering how they could survive such a devastating blow not just once but repeatedly without succumbing to despair. The only answer I could come up with, still not entirely satisfactory, was that the fragility of life in those days must have somewhat tempered their expectations.

Job or no job, there I was in Philadelphia. Clearly it was time to relinquish the ragged dream of an academic career in the humanities and rethink my future. Long story short, I accepted a position as the director of an oral history project on women physicians at the Medical College of Pennsylvania, which sparked an interest in scientific research, and my life veered off in a different direction.

By then I had heard not only from my daughter’s friend but from enough people around the world to realize that over the years my seemingly obscure dissertation had developed its own little cult following. The original document had been typed by a professional dissertation typist in 1974, with two photocopies deposited in the University of Pennsylvania Library and otherwise available only on microfilm. It occurred to me that if I was willing to pay to have the text word-processed, it could be more easily reproduced and thus made more readily accessible to both the casual and the serious reader. Had I known what I was getting myself and my two stalwart typists into—I with a more than full-time job doing grant-funded research in a scientific laboratory, my typists forced to deal with an unexpectedly difficult text full of archaic language—I probably would have abandoned the project then and there. But once started, there was no turning back, and by 1996 Dissertation 2.0 had been completed. Since then, it has been downloadable free of charge from the Penn Libraries Scholarly Commons and hundreds of people have done so.

More recently yet another revolution in book production has taken place, and through the miracle of indie publishing I am now able to provide the convenience and portability of a paperback version at a modest price. You are holding the results in your hand. I have corrected a few obvious typos—without, I hope, introducing too many more--improved the title, and added this new preface, but I have otherwise made only minimal changes in the text. I have moved on without regret from the life in academia to which I once aspired, and modern literary scholarship has undoubtedly taken our understanding of the history of women’s autobiography far beyond where I left this topic in 1974.

What I have not left behind is my abiding interest in women’s origin stories, reflected not just in my doctoral dissertation but in my subsequent work on the women physicians project and now in what I like to call my “post-professional career” of memoir- and essay-writing. I am not alone in this obsession. Memoir was recently described by Adam Gopnik in the Atlantic Monthly as “perhaps the leading genre of our time, much as the novel was for the first half of the twentieth century.” He cited the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Annie Ernaux, the first ever to a memoirist, as evidence of the ascendancy of the genre (though tell that to the members of my book club, or to the estimated five million book clubbers in the U.S.) This is a seismic shift. If nothing else, I hope my efforts to trace the emergence of the autobiographical impulse in women, and the underlying changes in prose style during the seventeenth century towards a less rhetorical and syntactically looser structure that lends itself to self-revelation, will continue to remind us not to forget where we came from if we hope to understand where we are.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed