Among the earliest feminist stirrings in my young psyche came when I challenged my eighth grade teacher to defend the use of "mankind"--and "man" and "men"--in the Declaration of Independence. Mr. Ward patiently explained that the word "mankind" was intended to include everyone, including women, that was just how the English language worked. I already knew from my own lived experience that this was not true, that I had at best a kind of step-relationship with "mankind," and I was having none of it. (Of course I eventually learned that even Mr. Ward's happy-talk version of history wasn't true on another level--that the writers of the Declaration of Independence and the framers of the Constitution never intended by implication to include women, or any people of color, or even poor white men, as equal beneficiaries of the rights for which they were so articulately arguing. But that is a topic for another day.)

When I later became an English major and then a graduate student in English literature, I became quite prescriptive about English grammar--no splitting infinitives for me! no subject-verb disagreements! Although I fully recognized that a living language must change, I also felt there had to be "experts" who served as the brakes to keep language from changing so fast that it interfered with communication; and it was now part of my sacred responsibility as a scholar to join ranks with these experts. But even then, because of my experience in the eighth grade, I made an explicit exception for sexist language and did my best to recognize and uproot it whenever I encountered it, as well as to seek out acceptable alternatives. (By the way, I have now gone over 99 percent to the non-prescriptive camp, though I still have to remind myself occasionally that English is not Latin, that many ungrammatical turns of phrase were once in regular use, that language change is driven more by the spoken than the written word. But that is also a topic for another day.)

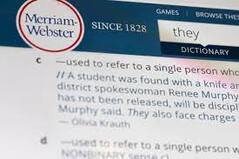

The reason it has generated so much interest, of course, and sparked such notoriety in our highly polarized society, is the rapid increase in its use as a third person singular pronoun, and the fact that people who identify as nonbinary are in the vanguard of those adopting its use. As Peter Sokolowski, Merriam-Webster's editor-at-large, put it, "[W}ith the nonbinary usage, people are sensing that it means something new or different, and they are going to the dictionary. When you see lookups for it triple, you know that ‘they’ is a word that is in flux.”

It's not something I'd ever have predicted way back when. The feminist moms of my generation favored unisex clothing for our kids. We bought toy trucks for our daughters and dolls for our sons. For the same reasons, we argued successfully for nonsexist nomenclature for professions like "firefighter" and "flight attendant." We achieved pretty much universal acceptance of the title "Ms", doing away once and for all with the implication that a woman's marital status was a critical definer of her role and her value.

And now, it would seem, those very sons and daughters have apparently raised a generation of humans an appreciable minority of whom decline to identify as either of the Big Two (in the process defining those born female as noncombatants in the still unfinished struggle for women’s rights). For all our apparent success with nonsexist language, it has not brought us where I think most of us expected—that is, to a rejection of confining stereotypes in favor of allowing everyone access to a full range of human possibilities—in other words, to a recognition that we are all, to a greater or lesser degree, nonbinary. Instead, significant swaths of Generation Z have ended up in a place where “nonbinary” is a third (or fifth or tenth) category from which the rest of us have been othered or excluded.

At the age of eighty I've lived long enough to know that some battles are resolved not because someone wins or loses but because the terrain has shifted under our feet. So I guess it's time to leave Gen Z to find its own way, linguistically speaking, hoping those whose pronouns are "they/them" will forgive our occasional verbal lapses to the despised "she" and "he."

Over the succeeding decades, many solutions have been advanced--"his or her", "s/he", alternating between "he" and "she", or recasting sentences altogether so that everything was in the plural, or so no pronouns were needed at all. Also in the mix was the singular "they," an option floated as early as 1980 by Casey Miller and Kate Swift in their groundbreaking Handbook of Non-Sexist Writing as a possible alternative to "he or she/his or hers." None, however, emerged as superior to all the rest, none fully satisfied prescriptive grammarians, and none fell trippingly on the tongue.

Attempts at inventing new gender-neutral pronouns, such as "xe/xem/xyr", "ey/em/eir", or even "hizzer", were also tried but fared even worse. In contrast to new nouns and new verbs, which we add to the English language regularly and with gusto, it is exceedingly rare to add new pronouns, even more so than adapting already-existing pronouns to new uses.

So there things stood, at an uneasy impasse, until the mid 2010s, when the popular press started allowing the singular "they" to creep in. The Washington Post got the ball rolling in 2015, followed by the Associated Press Stylebook in 2017. By 2019, the singular "they" had started appearing on so many people's radar that as noted above, it became Merriam-Webster's word of the year--not because we had finally settled on a satisfactory solution to the decades-old need for a substitute for the generic masculine but because of the much more recently felt need for a substitute when neither "he" nor "she" will do.

Once the singular "they" as a tool for inclusivity made its debut, scholars went back for a closer look and discovered that mirabile dictu, the construction is not so aberrant after all. The Oxford English Dictionary, the ultimate authority on the history of English usage, actually traces the singular "they" back to 1375. Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare both used it. It wasn't until the 17th century that prescriptive grammarians began decrying its use, but even then it can be found in the work of Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Henry James, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. And while they eventually largely prevailed in squelching the singular "they," these same grammarians failed spectacularly in their efforts to likewise expunge a similar yet oddly overlooked change to the second-person pronoun "you," which is now the same in both the singular and plural but had separate forms ("thou" in the singular, "ye" or "you" in the plural) from Old English though early modern English.

Furthermore, all but the most diehard purists already use the singular "they" in ways that we scarcely notice. When referring to someone whose gender is not known and can't readily be ascertained--for example, the driver who just cut you off--almost any native speaker will use the pronoun "they" (likely followed by a series of expletives). And anyone who ever uses a form of the third person plural pronoun when the antecedent is "someone," "somebody," "anyone," "everybody," "no-one," and so forth--e.g., "someone left their scarf in my car"--is guilty of using the singular "they."

As if on cue, the style manuals most frequently used to guide academic writing soon weighed in. The American Psychological Association, which prides itself on its commitment to eliminating gender bias from language, wholeheartedly welcomed the singular "they" in the seventh edition of the APA Publication Manual (2019/2020) when referring equally either to a generic person whose gender is unknown or irrelevant, or to a specific, known person who uses "they" as their pronoun. The 20th edition of the Modern Language Association's MLA Style Manual released at around the same time, also endorsed the singular "they" for "specific use" in referring to "a single person whose gender identity is nonbinary", and less enthusiastically as an acceptable though grammatically regrettable option for "generic use", offering a very long list of ways to avoid ever using it. The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) was even dodgier, relaxing in 2018 its former blanket prohibition of the singular "they"--suggesting instead that individual preference for the singular "they" be "generally" respected by writers but declining to take a clear stand on its use under any other circumstance.

Why, after decades of squirming by virtually everyone concerned about the consequences of the sexism embedded in the English language, were the felt needs of a relatively small handful of individuals able to effect, almost overnight, a seismic shift in how we speak, write, and think? How could the sound of the singular “they” suddenly become so normalized that it scarcely sounds odd even to an eighty-year-old woman?

Our newfound awareness of the singular “they” unquestionably started with the intriguing and controversial assertion that nonbinary is a separate category in which we can only claim membership by rejecting the gender our parents thought they were getting when we were born, whichever it might have been. And make no mistake, its adaptation to fill the resulting need for an apt pronoun, the so-called inclusive singular “they”, is a truly novel use of the construction and not one that emerged organically from the historical precedents cited by those nonprescriptive linguists who now seek to justify its acceptance.

Once that relatively limited application drew attention to this unprecedented use for the singular “they”, however, the spread of its use has desensitized even ears as old as mine to its former awkwardness, just as occurred not so very long ago with the normalization of the singular “you.” The inclusive singular “they” has thus functioned as a sort of linguistic camel’s nose being poked under the edge of the tent, offering a unique opportunity to welcome the rest of the camel into the tent. As Jean Reynolds wrote in her blog “Write With Jean,” on the MLA’s reluctant surrender: “[T]he inclusive issue isn’t the biggest reason for endorsing the singular they. Our primary goal should be getting rid of the clumsy his-or-her construction. Begone!”

If instead (as the CMOS seems to advise) we resist this accommodation and cede ownership of the singular "they" to a subgroup for a much more specialized purpose, we may miss forever a unique opportunity to embrace a badly-needed term that can apply not only to people self-identifying as nonbinary but also to any person of unknown or unspecifiable gender. Both/And--always a good solution.

But consider this sentence: "Each one of us will have our own special triumphs or tragedies to look back on." Although these words were uttered by Queen Elizabeth II in her Christmas message of 1969, they are definitely not an example of the "royal we," they are rather an example of a technically ungrammatical usage we ourselves might one day back ourselves into. Surely we don't want to replace "our" with "his," or "his or her," or even "their"? I think the queen’s usage would sound perfectly natural to most of us, so the singular “we” is already a thing, ready and waiting to take its place alongside the singular “you” and the singular “they.” But that is definitely a topic for another day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed